LAND OWNERSHIP PATTERNS AND EARLY DEVELOPMENT IN MIDDLE PLANTATION: REPORT OF ARCHIVAL RESEARCH

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 1724

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

2010

LAND OWNERSHIP PATTERNS AND EARLY DEVELOPMENT IN MIDDLE PLANTATION: REPORT OF ARCHIVAL RESEARCH

COLONIAL WILLIAMSBURG FOUNDATION

Department of Archaeological Research

February 2000

Re-issued

June 2004

Table of Contents

| Page | |

| INTRODUCTION | 1 |

| THE ORIGIN OF THE MIDDLE PLANTATION | 1 |

| Construction of the First and Second Palisade | 1 |

| The Maturation of Community Development | 5 |

| MIDDLE PLANTATION'S FIRST SETTLERS | 6 |

| Dr. John Pott | 6 |

| Lieutenant Richard Popeley | 7 |

| William Davis (Davies) | 8 |

| John Clarke | 8 |

| Robert Higginson | 9 |

| George Read (Reade) | 9 |

| George Lake | 10 |

| George Menefie (Minify) | 11 |

| THE KEMP-LUDWELL HOLDINGS | 12 |

| Richard Kemp | 12 |

| Thomas Hill | 17 |

| Thomas Ludwell | 17 |

| Philip Ludwell I | 18 |

| Thomas Ballard I and Thomas Ballard II | 19 |

| Governor Francis Nicholson | 20 |

| John Young | 21 |

| Cultural Features Potentially Associated the Ballard/College Tract | 22 |

| The Rev. James Blair | 22 |

| Archaeological Features Associated with the Rev. James Blair's Property | 24 |

| THE SAINES/PEALE/WEEKES LANDHOLDINGS | 24 |

| John Saines | 24 |

| Francis Peale | 24 |

| Robert Weekes | 24 |

| Cultural Features Associated with the Saines/Peale/Weekes Tract | 26 |

| THE BRAY HOLDINGS | 26 |

| James Bray I | 26 |

| Angelica Bray (Mrs. James Bray I) | 28 |

| Thomas Bray I (son of James Bray I) | 29 |

| David Bray I (son of James Bray I) | 29 |

| Ann Bray Ingles (daughter of James Bray I) | 30 |

| David Bray II (son of David Bray I) | 31 |

| James Bray II (son of James Bray I) | 32 |

| Thomas Bray II (son of James Bray II) | 32 |

| ii | |

| James Bray III (son of Thomas Bray II) | 34 |

| Elizabeth Bray Johnson (daughter of Thomas Bray II) | 36 |

| Bray Property Associated with the Ballard Family | 37 |

| Cultural Features Associated with the Bray Property | 38 |

| Benjamin Harrison Jr.'s Houses | 38 |

| THE CUSTIS FAMILY HOLDINGS | 39 |

| Daniel Parke (Park) II | 39 |

| John Custis IV | 40 |

| Cultural Features That May Be On the Custis Property | 42 |

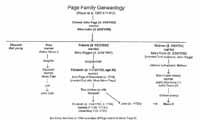

| THE PAGE LANDHOLDINGS | 42 |

| Colonel John Page | 42 |

| Francis Page (son of Colonel John and Alice Page) | 49 |

| Elizabeth Page Page (the daughter of Francis Page) | 52 |

| Elizabeth Page Bray (the granddaughter of Francis Page) | 52 |

| Archaeological Features Associated with Francis Page's 168 Acres | 53 |

| Archaeological Features Associated with Colonel John Page's Plantation | 54 |

| Archaeological Features Near the Wythe House | 54 |

| Archaeological Features in Duke of Gloucester Street | 55 |

| Publicly Owned Buildings on the Capitol Grounds | 55 |

| THE DYER FAMILY'S LANDHOLDINGS | 56 |

| William Dyer | 56 |

| Henry Dyer | 56 |

| BIBLIOGRAPHY | 57 |

INTRODUCTION

The reconstruction of land ownership patterns in that portion of Middle Plantation (later, Williamsburg) which originated in James City County is impeded by the loss of that jurisdiction's antebellum court records. However, four seventeenth century plats and a fifth that dates to the eighteenth century, all of which are associated with Rich Neck, provide data that are of critical importance in piecing together the boundaries of contiguous properties. Boundary descriptions included in deeds pertaining to two subsidiary parcels, severed from Rich Neck in 1699 and 1707, also are of immense value, as is a 1960 plat that includes part of Rich Neck's northwesterly boundary line. Patents, York County records, minutes of the colony's assembly, and a broad primary sources have been used throughout the research process, as have reports produced by other scholars. Collectively, all works provide important clues to the configuration of properties and how land ownership patterns evolved over time. This, in turn, enhances our understanding of Middle Plantation's cultural setting.

THE ORIGIN OF THE MIDDLE PLANTATION

Construction of the First and Second Palisade

The idea of building a palisade across the James-York peninsula first surfaced in 1611 when Sir Thomas Dale recommended that the peninsula be secured below the fall line (Brown 1890:I:503). In 1612 and 1613 Dale succeeded in planting several communities at the head of the James River, and sent word home that he intended to "knock up pales whither he should pleasure." All but one of the new settlements Dale established abutted the James River, and they were nucleated and surrounded by a defensive wall or palisade. In some instances, a palisade several miles in length cordoned off a substantial quantity of land adjacent to the settlement, setting aside land for the colonists' use in growing crops and pasturing livestock (Hamor 1957:31-32; Ferrar MS 40; Rolfe 1971:7-11).

After the March 22, 1622, Indian uprising decimated more than a third of the colony's population, survivors from outlying plantations were drawn into the eight settlements that were fortified and held. Virginia Company officials, though sympathetic to the colonists' plight, urged them to return to he property they had abandoned (Kingsbury 1906-1935:III:570, 612-613; IV:524). During the fall and winter of 1623, as their fears subsided, they gradually reoccupied their plantations and some people fortified their homes by surrounding them with palisades. Meanwhile, retaliatory raids were undertaken regularly to suppress the native population. Governor Francis Wyatt informed his superiors that "Our first worke is expulsion of the Savages to gaine the free range of the country for encrease of Cattle, swine &c., which will more than restore us, for it is indefinitely better to have no heathen among us." He added that "Our intent was after the Massacre to have seated the whole Colony, having runne a strong Palisade from Martins Hundred to Chesekacque, to Plant Pawmunka river also" (C.O. ⅓ ff 21-23) .1

2In another letter Governor Wyatt said

We know of no other course, then to secure the forrest by running a pallizade from Marttin's hundered to Kiskyack, which is not above six miles over, and plaecing houses at a convenient distance, with sufficient guard of men to secure the neckee whereby wee may gaine free from possibility of annoyance by the Salvages, a rich ceramite of ground contayneing littl less than 300,000 acres of land, which will feed nombers of people, with plentifull range for cattle [C.O. ⅓ ff 21-23].

In February 1624, when Captain John Harvey sent a report to the king, describing conditions in the colony, he proffered that in order to deal effectively with the Native population it was necessary "To plant Chiskiake scituat upon the Pamunkey River very strongly, and to run a pale from thence to Martins hundred, which will add safety, strength, plenty, and increase of cattle to the plantation and greate advantage" (Aspinwall et al. 1871:72) . Thus, those who had firsthand knowledge of the colony sand the Natives were in general agreement that construction of a palisade across the peninsula would be highly beneficial.

In 1626 Samuel Mathews and William Claiborne presented a proposal for "the winning of the forest." They offered to build a palisade within 18 months or less that had "convenient houses within commaund of muskett shott one of another" and to place sufficient number of men "to guard ye same and to defend it against ye incursion of ye salvages." The two men sought 1,200 pounds sterling for their initial work, plus a grant of six score yards [360 feet] of land on each side of the palisade. They offered to see that men stood guard and that the houses they built were maintained, in exchange for a fee of 100 pounds a year (C.O. ¼ f 28). Mathews' and Claiborne's proposal was rejected.

After Governor John Harvey took office, the issue of building a palisade again came to the forefront. On May 29, 160, he sent word to England that "Our first workke is expulsion" of the Indians. He said that the colonists intended "to plant Cheskeyack, a place situate upon Pamunkey, whereby we hall face our greatest enemie… and disable the Salvages to annoy us or hinder the free range of our cattle in the forest" (C.O. 1/5 f 195) . Thus, the maintenance and preservation of livestock was an important consideration and a recurrent theme from 1611, on. In 1630 Captains John West and John Uty established plantations near the mouths of Queens and Kings Creeks in Chiskiack and Captain Toby Felgate seated land to their east (Nugent 1969-1979:I:14-15, 22, 90-91, 122). During the early 1630s settlement spread east to Wormeley Creek.

In February 1633 the assembly agreed that a palisade should be built across the James-York peninsula, setting aside an area for the colonists' exclusive use. Fifty acres were offered to every free man willing to settle between Queens and Archers Hope (College) Creeks before May 1, 1633. On March 1, 1633, a group of men was supposed to meet at Dr. John Pott's newly built house in Harrop, from which they were to set out and. commence work (Hening 1809-1823:I:208-209). Construction began and within a relatively short time, the first palisade was built. It was then that a small settlement took root at Middle Plantation, the broad ridge between the heads of Queens and Archer's Hope (College) Creeks (McIlwaine 1924:192; Nugent 1969-1979:I:22, 89, 91, 94, 143, 160-161, 249, 323, 388, 515). In July 1634 Governor John Harvey informed the Privy Council that he had "secured a great part of ye Country from ye incursion of the natives with a strong pallisado which I caused to be built between two creeks, whereby they have a safe range for their cattle near as big as Kent" (C.O. 1/8 f 74) . No documentary 3 information has come to light that indicates what the first palisade was like. It may have had "convenient houses within commaund of muskett shott one of another," like the one Samuel Mathews and William Claiborne: offered to build in 1626, or it may have been of an entirely different design.2

A preliminary study of early patents reveals that during the 1630s a few individuals, such as Richard Popeley, George Menefie, and William Davis (Davies) came into possession of vast tracts of land (1,200 acres or more) that were adjacent to the palisade or the horsepath that ran through Middle Plantation. This raises the possibility that they were actively involved in the defensive wall's construction and received land as compensation. Popeley owned land on both sides of that portion of the palisade which later bisected Williamsburg and served as a boundary line for Colonel John Page's 280 acre patent (see ahead). Popeley quickly subdivided and sold his 2,500 acres of land that straddled the palisade. In 1646, when John Clarke's administrator assigned Robert Higginson some of the land the decedent had bought from Popeley, reference was made to three rectangular parcels that abutted the upper (northwest) side of the palisade as it extended toward Queens Creek. Likewise, on the lower (southeast) side of the palisade were two long, narrow, rectangular parcels that contained 100 acres apiece. They had belonged to Richard Popeley, who in 1641 had sold them to Thomas Gregory and Thomas Lucas. Each of these tracts, which were contiguous, extended or 100 poles (165 poles) along the palisade and would have been 2,640 feet in length. A survey made for Richard Kemp in 1643 reveals that a series of long, narrow, rectangular tracts also flanked that portion of the palisade which extended toward the head of Archer's Hope Creek. It was here that Francis Peale, John Bates, Thomas Hill and William Davies had property. Patent research suggests that the two main sections of the palisade intersected in Middle Plantation, at a point on Nassau Street between Prince George and Scotland Streets. In that vicinity, where the defensive wall executed a sharp turn, was a tract called the Middle House, a term suggesting that a noteworthy structure (perhaps a blockhouse) was present near the palisade's midpoint. As Middle Plantation became more populous, most of the large patents near or abutting the palisade were subdivided into smaller parcels that were leased to tenants or sold. Some people, such as Robert Guy, Stephen Hamblyn, Edward Whitakers, Richard Davis, John Saines, and William Watts had lesser-sized tracts (usually 50 to 100 acres) which they enlarged (or disposed of) as time went on (Nugent 1969-1979:I:95, 102, 105-106, 110, 112-113, 123, 142, 147, 160, 204, 225, 316; II:261; Patent Book 1:132, 730; 2k.5,, 58-59; 4:101-102; York County Deeds, Orders, Wills 2:122).3 Land records suggest that even though Richard Popeley and others were assigned acreage on account of their service to the colony, they (like other patentees) were obliged to develop it in order to secure their title.

4Thomas Yonge, who visited the colony in 1634, praised Harvey's numerous accomplishments, citing his building a palisade across the peninsula and fortifying Old Point Comfort. He also said that settlement in Virginia had been greatly strengthened thanks to Harvey's efforts (Aspinall et al. 1871:102, 107-108, 111-112). However, Harvey had such heated disagreements with is councillors that on April 28, 1635, they turned him out of office. While the deposed governor awaited transportation to England, he was detained at George Menefie's country home near MiddlPlantation, Littletown, later known as Rich Neck (McIlwaine 1924:481; Sainsbury 1964:1:207, 212; C.O. 1/8 ff 166-167; ⅓2 f 7; Hening 1809-1823:I:223; Neill 1996:118-120; Aspinall 1871:150; Devries 1857:74).4 Despite the seriousness of the allegations against Harvey, the Privy Council reinstated him as governor, for it was believed preferable to uphold the king's authority than to acquiesce to popular pressure (Sainsbury 1964:1:208, 212, 216; C.O. 1/8 f 170ro). Sir John Harvey had long since left office when the palisade at Middle Plantation was rebuilt.

In 1644, the Natives responded to the growing pressure upon their land by rising up in defiance. This second major uprising occurred on April 18, 1644, and claimed 400 to 500 settlers' lives. Hardest hit were those who lived along the upper reaches of the York River and on the lower side of the James, near the Nansemond River. Afterward, the Grand Assembly resolved to "abandon all formes of peace and familiarity" with the Natives and retaliatory marches were undertaken for the expressed purpose of destroying the Indians. Eighty men were garrisoned at Middle Plantation and "all private trade, commerce, familiarity and entertaynment with the Indians" was prohibited, for governing officials believed that the weapons the Natives had used were procured through trade (Force 1963:II:3:1; Beverley 1947:60-61; Hening 1809-1823:I:-239, 290; McIlwaine 1924:277, 296, 501; Stanard 1915:229).

Retaliatory marches were undertaken against the Indians implicated in the uprising and the charismatic paramouit chief Opechancanough was captured and slain. In 1645 and 1646 forts or checkpoints were built at sites that provided access to the James-York peninsula and in October 1646 the Natives signed a peace treaty with Virginia's governing officials, agreeing to abandon the territory east of the fall line. By that date, construction of a new palisade at Middle Plantation already had gotten underway. York County records reveal that in November 1646 several men were fined for their delinquency "in sending a man to the Middle Plantation for work in setting up a pale there, whereby Robt. Higginson was forced to put a man in his room" (York County Deeds, Orders, Wills 2:189) . It is uncertain whether the men working under Captain Robert 5 Higginson's direction installed new pales where the 1633 palisade had stood, or utilized a somewhat different trajectory. Patents dating to the 1630s and 40s merely refer to "the palisade" and in 1655 one person's property reportedly was close to the "old pale." Another mentioned the palisade and the trench associated with it (Nugent 1969-1979:I:102, 105-106, 110, 112, 143, 161, 167, 186, 221, 242, 266, 272, 316).

The Maturation of Community Development

In 1678 the vestry of Bruton Parish decided to build a new brick church at Middle Plantation rather than replacing two older houses-of-worship that served the upper and lower parts of the parish. Donations were solicited. It was then that Jon Page, whose land later became part of Williamsburg, gave 20 pounds sterling and the ground upon which the new church was to be built. Other donors included Thomas and Philip Ludwell I, Otho Thorpe, and the parish clergyman, the Rev. Rowland Jones (Meade 1992:I:147).

On February 8, 1693, King William and Queen Mary granted a charter to the College of William and Mary. Later in the year, 330 acres of James City County land were purchased from Thomas Ballard I, acreage that he had acquired from the Ludwells. The new college's campus was located west of "the church now standing in Middle Plantation old fields." It extended to Archer's Hope Swamp (at the head of College Creek), followed the forerunner of Richmond Road, and straddled the track of Jamestown Road. Within months, a grammar school had opened "in a little School-Horse" close to the site where the college's main building was to be erected and in August 1695 the first bricks were laid for what became known as the Wren Building (Hening 1809-1823:III:122; Kornwolf 1989:35-36, 67; Beverley 1947:266; Hartwell et al. 1964:71).

By 1699 a small community, which consisted of a church, an ordinary, several stores, two mills, and a smith's school had grown up at Middle Plantation, near the college. On April 27, 1699, the colony's assembly convened at the college because the statehouse at Jamestown had been destroyed by fire. A few days later, a group of students urged the burgesses to make Middle Plantation the colony's capital, pointing out that the site was well suited for trade and that the college's presence would attract tradesmen and other skilled workers (Reps 1972:141-142).

With relatively little deliberation, the burgesses passed "An Act Directing the Building the Capitoll and the City of Williamsburgh," which was named for King William, the Duke of Gloucester. The 220 acre town site, which was situated at Middle Plantation, straddled the line between James City and York Counties, enveloping a substantial portion of John Page's 280 acre patent. Duke of Gloucester Street, which ran along th ridge back that separated the drainages of the James and York Rivers, formed the central axis of the new town, which was to be laid out regularly into half-acre lots. Provisions were made for Williamsburg to be served by two landings or inland ports: Queen Mary's Port on Queens Creek in York County and Princess Anne's Port on College Creek in James City County (Hening 1819-1823:III:197, 419-432).5 Theodorick Bland, who in 1699 was commissioned to lay out Williamsburg and its ports, along with the roadways 6 that linked them (the forerunners of Capitol Landing Road and South Henry Street), produced a detailed plat.6 To curb th. appetite of real estate speculators, the burgesses stipulated that no lots would be sold before October 20, 1700, "to the end that the whole country may have timely notice of this act and equal liberty in the choice of the lots." The new community was destined for success, for the spread of settlement inland was accompanied by steady growth in Virginia's population. In September 1701 the governor's council authorized compensation for those whose land had been taken for the new city.7 A few months later, a Swiss visitor observed that Williamsburg was "staked outt to be built." He said that a "church, college and statehouse, together with the residence of the Bishop [Commissary] some storehouses and houses of gentlemen and also eight ordinaries or inns, together with the magazine" already were in existence (Hinke 1916:26).

In October 1705 when the third in a series of town-founding acts was passed by the colony's assembly, the 1699 legislation that had established Williamsburg and its sister ports was reaffirmed. This time, provisions were made to control how the town would be developed. In 1705 the layout and dimensions of Williamsburg and its landings were described precisely as they had been in the text accompanying Theodorick Bland's June 2, 1699, survey. Trustees were appointed and authorized to sell the town's lots, which had to be developed within 24 months of the date of purchase or be forfeited. The size of Williamsburg's lots was proscribed by law and restrictions were placed upon the dimensions, character and placement of the buildings that lot owners could erect. Structures built along Duke of Gloucester Street had to conform with height and set-back rules. The lots in Queen Mary's and Princess Anne's Ports were no more than 60 feet square and "a sufficient quantity of land at each port or landing place" was left as a commons (Hening 1809-1823:III:419-431; Bland 1699). Merchants, planters, artisans and ordinary-keepers were among those who owned and developed lots in Williamsburg and its sister ports and some people had one or more lots in both places. Between 1715 and 1721 the seat of the James City County court was moved to Williamsburg and a county courthouse was built there.

MIDDLE PLANTATION'S FIRST SETTLERS

Dr. John Pott

Dr. John Pott, the colony's Physician-General, came to Virginia in 1621 with Sir Francis Wyatt, the incoming governor. Pott was accompanied by wife Elizabeth, two servants and two surgeons. The Virginia Company, which outfitted Dr. Pott and sent him and his household to the colony, described him as "well practiced in surgery and physics" and skillful in the treatment of contagious diseases. During the 1620s, while he was a councillor, 7 he patented a large lot in urban Jamestown and secured a leasehold in the Governor's Land (Patent Book 1:3; Nugent 1969-1979:I:2; Stanard 1965:30).

Dr. John Pott, despite his credentials as a physician, was described by Treasurer George Sandys as a "pitiful counselor" and "a cipher." Sandys said that he enjoyed the company of his inferiors, "who hung upon him while his good liquor lasted." Pott also seems to have had some serious ethical problems. In 1626, he was sued by one of his indentured servants, whom he had agreed to teach the apothecary's art and then refused to. A Martin's Hundred woman, captured by the Indians during the 162 uprising and detained for several months, claimed that although Dr. Pott had redeemed her with some glass beads, he kept her in greater slavery than the Indians had. Perhaps Dr. John Pott's most unsavory act was his involvement in the poisoning of a group of Indians, who had just signed a peace treaty. As a result, he was temporarily removed from office. Later, he was named a councillor (McIlwaine 1924:3-4, 117; Kingsbury 1906-1935:II:481; III: 565; IV:64, 110, 473; C.O. ⅓ f 94).

In March 1629 Dr. John Pott's fellow councillors elected him deputy governor, for Captain Francis West, who had filled the vacancy created by Sir George Yeardley's death, went to England. Pott sent William Claiborne into the Chesapeake on a voyage of exploration and authorized him to trade with the Dutch and other English colonies. He appointed local commissioners to try cases involving minor disputes and he sought to strengthen the colony's defenses. He acquired some acreage in Harrop, seven miles from Jamestown, and a patent in nearby Elizabeth City. When Sir John Harvey arrived in the colony to assume the governorship, he promptly placed Dr. John Pott under house-arrest at his plantation called Harrop, for he was known to have pardoned a convicted murderer and was accused of stealing cattle. Mrs. Elizabeth Pott, who remained steadfastly loyal to her husband, went to England to assert his innocence (McIlwaine 1924:182, 190, 479, 48 ; C.O. 1/5 f 203, 210, 234; 1/6 ff 36-37; ⅓9 ff 114-115, 117-111; Nugent 1969-1979:I:15; Sainsbury 1964:1:116-118, 133; Stanard 1965:14).

During the early 1630 Dr. John Pott's relationship with Governor John Harvey deteriorated markedly. According to Richard Kemp, Pott was angry because Harvey had removed his brother, Francis, as commander of the fort at Old Point Comfort. Kanp may have described the situation accurately, for in April 1635, when Harvey was arrested by his councillors, Dr. John Pott was one of the prime movers (C.O. 1/8 ff 166-169; Sainsbury 1964: 207, 212; McIlwaine 1924:480).

Lieutenant Richard Popeley

In 1638 Richard Popeley patented two 1,250 acre tracts of land at Middle Plantation. One was located in Charles Riser (York) County, near the head of Queens Creek, on the northwest (or upper) side of the palisade that had been built in 1633. This Popeley tract, which extended in a northwesterly direction into the woods, abutted south-southeast upon land that was owned by Edward Whittakers, whose land also was on the upper side of the palisade (Patent Book 1:667). Popeley's other tract was in James City County, at the head of Archer's Hope (or College) Creek, on the southeast (or lower) side of the palisade (Patent Book 1:635, 667). Within two years' time, Richard Popeley began disposing of his property. In 1642 he sold 400 acres on the southeast side of the palisade to George Lake and George Wyatt, who were coopers and business partners, and he conveyed 8 100 acres to Nicholas Wattkins, acreage that reportedly abutted west upon the palisade, north upon the land of George Lake, and south upon the land of Captain Francis Pott, Dr. John Pott's brother and heir (Patent Book 2: 54-56, 59; C.O. 5/1389 ff 66-68). Land records disclose that the Popeley land on the east side of the palisade eventually became part of the Page and Bray families' landholdings and that Nicholas Wattkins' acreage was acquired by Thomas Ballard I, who sold part of it to David Bray I (see ahead).

During the 1640s Richard Popeley (and later, his widow and executrix, Elizabeth) disposed of much of his property on the northwest side of the palisade (York County Deeds, Orders, Wills 1:112-115; 3:53-54, 108, 131; 6:422; 8:449-452). Richard Popeley probably seated part of his Middle Plantation landholdings, for in June 1640 he was accused of killing a bull that belonged to John White, whose acreage eventually became the northeastern part of the Rich Neck tract and a 68 acre parcel owned by Francis Page (York County Deeds, Orders, Wills 5:65; McIlwaine 1924:477; Beverley 1678) (see ahead).

William Davis (Davies)

In June 1639 William Davis received a patent for 500 acres of land in Archer's Hope, between the horsepath8 that ran through Middle Plantation and the head of Archer's Hope Creek. The land Davies patented abutted north northwest upon the patent of George Lake and George Wyatt and south southwest upon the acreage of Dr. John Pott. When Governor William Berkeley arrived in Virginia he reaffirmed the patent William Davies had received in 1639 (Patent Book 2:51). Davis's patent description suggests that is acreage was located in the neck of land defined by College and Papermill Creeks. During the mid-1640s Governor Berkeley grantee William Davis 1,200 acres of land near the head of Archer's Hope Creek, which included Dr. John Pott's plantation that had descended to his brother, Francis, by right of inheritance. The descriptive information included in the Davis patent reveals that the Pott plantation was located in the neck of land bound on the west by Archer's Hope (College) Creek and on the east by the Weir (Ware) branch of Halfway Creek (Patent Book 2:367). In 1643 when surveyor John Senior (1643) prepared a plat of Secretary Richard Kemp's property, Rich Neck, he identified a 50 acre tract along the west side of the palisade that had been assigned to Captain Francis Pott on June 13, 1642, which Pott had conveyed to William Davis. In December 1656 William Davies' 1,200 acres came into the possession of John Bromfield, who married Davies' widow and patented the decedent's land (Nugent 1969-1979:1:336).

John Clarke

In 1646 Edward Wyatt, the late John Clarke's administrator, brought suit against Captain Robert Higginson, the man who had overseen construction of the second Middle Plantation palisade. At issue was possession of some of the late John Clark's land, which 9 was then in Wyatt's possession. Higginson was allowed to keep the house in which he then resided, plus a tobacco house, and to "take up for himself" a parcel that measured 100 poles (1,610 feet) in breadth that adjoined Edward Wyatt's land, which was 50 poles (825 feet) wide and abutted acreage that was owned by Henry Taylor and Nicholas Brooke (York County Deeds, Orders, Wills 2:122). A patent that Robert Higginson's daughter and heir, Lucy, received in 1652 reveals that John Clarke's land was on the northwest side of the Middle Plantation palisade (Patent Book 1:132).

Robert Higginson

In 1646, Captain Robert Higginson, who was residing in Middle Plantation, was awarded a 32 acre parcel in Charles River (York) County. It abutted the east side of northerly section of the palisade that extended toward Queens Creek. He was then living upon an adjoining parcel that belonged to the late John Clarke where he had a dwelling and a tobacco house (York County Deeds Orders, Wills 2:122). Higginson also owned some acreage in James City County, in the vicinity of Tutteys Neck. During the summer of 1646, Higginson was responsible for seeing that the palisade that ran through Middle Plantation was rebuilt. Perhaps in payment for his work, he was awarded 100 acres of the late John Clarke's land, part of the 850 acres that the decedent had purchased from Lieutenant Richard Popeley (York County Deeds, Orders, Wills 2:142, 148, 167, 189; 6:422).9

Robert Higginson's daughter, Lucy, was his only surviving heir. She successively wed Lewis Burwell I, William Bernard, and Philip Ludwell I. While married to Burwell and Bernard, she sold of portions of her late father's property at Middle Plantation to George Read and others (York County Deeds, Orders, Wills 1:160 161, 164, 172; 3:11; 6:422). At least 150 acres of Lucy's inherited property at Middle Plantation came into the hands of Colonel John Page before she married Philip Ludwell I.

George Read (Reade)

George Read (Reade), who came to Virginia in 1637 with the reinstated Governor John Harvey, resided in his dwelling at Jamestown. In February 1638 he wrote his brother, Robert, that he would not have survived without the numerous favors he had received from Harvey and Secretary Richard Kemp. After Harvey's removal from office, George asked Robert to use his influence to see that he was named Secretary of the Colony, if Kemp vacated that position. In August 1640, George Read received the appointment and shortly thereafter, married Nicholas Martiau's daughter, Elizabeth. When Richard Kemp made his will in 1649, he asked his executors to grant George Read 50 acres in the Barren Neck where he (George) then lived.10 In 1648 George Read became clerk of the council and in 1658 he was designated a councillor. As a burgess, he represented 10 James City County in the 1649 session of the assembly and he served on behalf of York County in 1656. During the 1650s George Read purchased some of the late Robert Higginson's land from his daughter and heir, Lucy, and sold it to Colonel John Page. Some of that property later became part of the city of Williamsburg. When George Read made his will in September 1670, he was living in York County. In 1691 part of what had been his home tract became the town of York (C.O. 1/9 ff 188ro, 209r0-210vo; 1/10 f 176; Sainsbury 1964:1:264, 309, 311, 314; Meyer et al. 1987:419-421; McIlwaine 1924:473; Hening 1809-1823:I:358-359; Withington 1980:323; McGhan,1993:775; Coldham 1980:34).

George Lake

In April 1642 George Lake and his partner, George Wyatt, both of whom were coopers, purchased 400 acres of land from Lieutenant Richard Popeley. Their acreage, which was rectangular in shape, lay upon the lower side of palisade at Middle Plantation and extended in a southeasterly direction toward the head of Archer's Hope (College) Creek.11 The two men also acquired an adjacent acre parcel (called the Middle House) from Thomas Lucas and Thomas Gregory, who had bought their land from Popeley in February 1641 (Patent Book 2:56).12 These two land acquisitions gave George Lake and George Wyatt control of 500 acres that extended from the eastern limits of Richard Kemp's Rich Neck tract, which was defined by one section of the palisade, northward to another section of the palisade that ran on a northeasterly axis. In October 1645 Lake and Wyatt decided to partition their property, which they subdivided and repatented. George Lake confirmed his title to 250 acres, the easterly portion of the jointly owned tract, whereas George Wyatt took the westerly portion, abutting Secretary Richard Kemp's land (Patent Book 2:54, 56, 58-59) (see the map "Middle Plantation, 1699/1700").

George Lake also invested in two other pieces of property at Middle Plantation. Sometime after 1639 he acquired 50 acres of land on the west side of the palisade, close to the site where the section of the pale that defined the east side of the Kemp and Saines patents executed a sharp northeasterly turn. In August 1661 Lake assigned his parcel to George Wyatt, whose son and heir, Henry Wyatt, sold it to John Page in 1672 (York County Deeds, Orders, Wills 5:1).13 The Wyatt tract, which bordered the road to New Kent County, abutted east upon a 50 acre parcel that John Bates bought from George Lake sometime prior to 1655 and south upon a 68 acre tract that was owned by John White (see "Middle Plantation, 1699/1700").14 In 1674 Colonel John Page purchased 11 the Wyatt and Bates parcels, which he combined with 68 acres he bought from John White Jr., and bestowed upon son Francis Page (Patent Book 3:337; York County Deeds, Orders, Wills 5:1, 65; 6:128; Beverley 1674, 1678). As George Lake's name is conspicuously absent from York County records, it is likely that he resided in James City County.

George Menefie (Minify)

George Menefie, who immigrated to Virginia during the early 1620s, patented a lot in urban Jamestown, acreage upon which he already had built a house. His lot, which was on the waterfront, abutted those of fellow merchants and political officials (Patent Book 1:6; Hotten 1980:175; Meyer et al. 1987:33). Menefie's name appeared in official records numerous times during the 1620s, for he served on juries, participated in inquests and practiced law. His on-going working relationship with the Bennetts of Warresqueak raises the possibility that he was tied into their London-based trading network. He had business dealings with John Pountis and Edward Blaney (who also were Jamestown merchants) and the Blands, who were important London merchants. In August 1626 George Menefie was identified as the official merchant and factor of the corporation of James City, a position that drew a 12 percent commission. The area for which he was responsible spanned both sides of the James River and extended from Skiffs Creek, westward to a point above the Chickahominy River. In October 1629 Menefie was Jamestown's burgess (McIlwaine 1924 :4-5, 9, 20-21 30, 47, 55, 58, 81-82, 109, 117-118, 122, 128, 133, 156, 165, 187; Sainsbury 1964:1:61; C.O. ⅓ ff 63-64, 210; Stanard 965:54).

In July 1635, George Menefie patented 1,200 acres at Rich Neck, acreage he had developed into a plantation known as Littletown; he confirmed its title on February 23, 1636 (Patent Book 4:199; Nugent 1969-1979:I:24, 50). Like many other Virginians, he apparently seated his property before he patented it.15 Through intermarriage with Isabell Perry around 1637, Menefie acquired land in Charles City County, which he made into a family seat called Buckland. In 1638 he sold his 1,200 acre Littletown tract to Secretary Richard Kemp, along with his 840 acres known as The Meadows, which abutted the horsepath that led to Middle Plantation. During the early 1640s he secured a patent for 3,000 acres on the north side of the York River, part of which later became the plantation known as Rosewell (Patent Book 1:740; Nugent 1969-1979:I:24, 54, 104-105). George Menefie, one of Virginia's most highly successful merchants and planters, was a member of the Governor's Council from 1635 to 1644 (Stanard 1965:33). When Dutch mariner David Devries visited Menefie's Littletown plantation in March 1633 he described its elaborate gardens and identified his host as a great merchant. (Devries 1857:34). The Council convened at Littletown on May 11, 1636 (McIlwaine 1924:491).

In April 1635 while George Menefie was a councillor, the dialogue between Governor John Harvey and his council became extremely terse. On one occasion, Harvey struck Menefie upon the shoulder, accused him of treason, and ordered his arrest. The other councillors refused to take Menefie into custody and instead, arrested Harvey and turned him out of office. Menefie was reluctant to charge Harvey with high treason, but 12 retained him at Littletown until he could be transported back to England. In mid-January 1637, when Sir John Harvey returned to Virginia, his governorship restored, he had George Menefie and several other councillors sent to England as prisoners and confiscated their goods. Menefie professed his innocence and was released after two months detention. When he returned to Virginia he brought many servants and again began serving as a councillor (McIlwaine 1924:480-481, 498; Sainsbury 1964:1:207, 212, 217, 252, 256, 264, 281, 314; Lower Norfolk County Book A:59; Neill 1996:118-120; Aspinall 1871:150; C.O. 1/9 f 134; 1/10 f 190; ⅓2 f 7).

George Menefie probably was living at Buckland during the late 1630s when he took a Tappahanna Indian boy into his home, reared him in the Christian faith, and received a stipend for doing so. In 1640, Menefie had in his custody two runaway servants, one of whom belonged to the Governor of Maryland. In February 1645 he and Richard Bennett were authorized to purchase powder and shot for use in defending the colony from the Indians (McIlwaine 1924:466, 477; Hening 1809-1823:I:297).

On December 31, 1645, when George Menefie made his will, he mentioned his fourth wife, Mary, and daughters Mary and Elizabeth. He bequeathed his land in Jamestown to his daughter, Elizabeth, who by that date had married her step-brother, Henry Perry, and he made reference to his ships, the Desire and the William and George. He left a sum of money to Jamestown merchant John White and asked to be buried in the cemetery at Westover Church. George Menefie died shortly thereafter and his will was presented for probate in London on February 25, 1646 (Stanard 1965:3 ; Meyer et al. 1987:449; Withington 1980:180; McIlwaine 1924:383).

THE KEMP-LUDWELL HOLDINGS

George Menefie, who called his plantation Littletown, first patented the property that his successor, Richard Kemp, named Rich Neck. After Kemp's death, his widow and daughter inherited his property. The widowed Elizabeth Kemp and her new husband, Sir Thomas Lunsford, made their home at Rich Neck. Later, the plantation was owned by several members of the Ludwell family. Within the discussion that follows, only Rich Neck's location, principal owners, and the configuration of its boundaries will be addressed.

Richard Kemp

Richard Kemp, a native of Gilling in Norfolk, England, immigrated to Virginia sometime prior to 1634, at which time he was named a councillor and Secretary of the Colony. He was married to Elizabeth, the daughter of Christopher Wormeley I and niece of Ralph Wormeley, one of Virginia's wealthiest and most influential planters. In September 1634 Kemp dispatched a petition to the king, asking to be assigned some office land as part of his stipend, and later, he requested indentured servants and livestock (Withington 1980:323; McGhan 1993:775; Coldham 1980:34; C.O. 1/8 f 90; Stanard 1963:21, 32; Sainsbury 1964:1:191, 207).

Secretary Richard Kemp's official correspondence indicates that he was steadfastly loyal to Governor John Harvey during the 1630s, when Harvey was at odds with his council. Kemp clashed openly with York County clergyman Anthony Panton, who 13 held him up to public ridicule and poked fun at his coiffeur. On May 17, 1635, Kemp dispatched a letter to the king's commissioners in which he described Governor Harvey's April 28th ouster from office and cast blame upon Dr. John Pott as instigator (C.O. 1/8 ff 16-169; McIlwaine 1924:481).

While Sir John Harvey was in England lobbying for reinstatement as governor, Richard Kemp continued to serve as Secretary and promoted some of Harvey's policies. On April 11, 1636, he asked that Virginia merchants be allowed to export commodities freely and that incoming goods be sent to three stores. He also proposed that a customhouse be established in Virginia. After Governor Harvey was back in power, Kemp was made customs officer, a position that yielded handsome fees (Sainsbury 1964:1:232, 263, 287-288).

On November 14, 1637, Secretary Richard Kemp obtained a patent for 600 acres of land in Archer's Hope, in James City County. It was part of his stipend as secretary (and that of "his successors forever"), not personally owned land. Cited was an October 5, 1631, court order, which stated that "600 acs. scituate as neare James Citty as might be conveniently be found" was to be set aside for the Secretary of the Colony. During February 1638 Kemp sought to obtain the 20 indentured servants and the cattle he claimed were part of the Secretary's stipend (Nugent 1969-1979:I:75; Patent Book 1:496; Sainsbury 1964:1:263).

Sir John Harvey was back in office on January 3, 1638, when Secretary Richard Kemp purchased George Menefie's 1,200 acre plantation called Littletown. Kemp, when patenting the Menefie acreage, called it the Rich Neck and noted that he also had acquired 100 acres near the Middle Plantation palisade on the basis of two headrights. Two months later Kemp patented 840 acres of contiguous land called The Meadows, which he bought from George Menefie. It abutted the horse path at Middle Plantation and lay north and west of the other land he had purchased from Menefie (Nugent 1969-1979:I:24, 54, 104-105). Richard Kemp's acquisition of The Meadows gave him a total of 2,140 contiguous acres that he owned outright. He also was in possession of 600 acres called the Secretary's land, which he patented on November 14, 1637 (Nugent 1969-1979:I:75). It was supposed to belong to Kemp "and to his Soccessors forever." Kemp's claim that the Secretary's Land was unproductive is supported by its description as "The Barren Neck" (Ambler MS 3; Sainsbury 1964:I:288).

On August 1, 1638, Secretary Richard Kemp patented a ½ acre lot in Jamestown, property hie had to improve within 6 months of risk forfeiture (Patent Book 1:587-588; Nugent 1969-1979:I:95; Ambler MS 2). By January 18, 1639, he had constructed a brick house that Governor John Harvey said was "the fairest ever known in this country for substance and uniformity" (Sainsbury 1964:1:287-288; Ambler MS 34) . Richard Kemp continued to correspond with officials in England and to give strong support to Governor Harvey. He sent word that although Virginians still planted too much tobacco, people were building good houses, raising cattle and hogs, and planting gardens and orchards. He said that money was being raised to build a statehouse and that tobacco was being sent to England to procure skillful workmen. He noted that the Indians were standing by, ready to do the colonists injury at every opportunity. Kemp's report on the status of the colony was certified by the council, an indication of its authenticity (Sainsbury 1964:1:263, 268; McIlwaine 1905-1915:1619-1660:126; C.O. 1/9 f 228ro, 242ro).

14In early April 1639 Kemp sought permission to return to England and said that a new governor, Sir Francis Wyatt, was expected daily. When Wyatt arrived and a new council tool office, Kemp was suspended as secretary. Afterward, Kemp claimed that the Wyatt administration had "persecuted" the old councillors and be said that Harvey's estate had been seized. With Thomas Stegg I's help, Richard Kemp slipped away to England, where he arrived on August 1640. He angered Virginia officials by absconding with some of the colony's official records. Kemp asked Lords Baltimore and Maltravers (two of the king's favorites) to defend him against allegations made by the controversial Rev. Anthony Panton (Sainsbury 1964:1:263-264, 268, 274, 289, 293, 310-311, 314; McIlwaine 1924:432-483, 495; C.O. 1/10 f 160).

In 1643, after Governor William Berkeley took office., Richard Kemp became a member of his council and again was made Secretary of the Colony. In June 1644, only two months after a major Indian uprising claimed nearly 400 lives, Kemp was named acting governor. He held office while Berkeley was in England, seeking assistance for the colony. In February 1645, Kemp informed Sir William Berkeley that construction of his brick houses at Green Spring and Jamestown (the rowhouse known as the Ludwell Statehouse Group) were progressing well. He also reported upon the construction of forts or surveillance posts on the fringes of the frontier, blockhouses intended to restrict the Indians' access to the colonized area (Lower Norfolk County Book A:178, 246; Stanard 1965:15; McIlwaine 1924:501, 562-563; Kemp 1645). After Sir William Berkeley returned to Virginia, Secretary Richard Kemp was granted the privilege of appointing all county clerks of court and the right to set their pay. As Kemp drew part of his compensation from clerks fees, the privilege Berkeley bestowed upon him was a potentially lucrative one. Kemp continued to serve as a councillor through 1649, at which time he acquired 3,530 acres on Mobjack Bay from Ralph Wormeley I (Lower Norfolk County Book B:6, 37, 70, 87, 112; Nugent 1969-1979:I:182).

On April 17, 1643, Richard Kemp repatented Rich Neck and its other holdings and laid claim to an additional 2,192 acres, to which he was entitled on the basis of 44 headrights. This gave him an aggregate of 4,332 acres (Nugent 1969-1979:I:143). Kemp's April 1643 patent stated that 600 of the 1,200 acres he had acquired from George Menefie already had been conveyed to Mr. Thomas Hill, who was responsible for whatever quitrent was due. Significantly, Hill's land consisted of two parcels, one of which was in the northeast corner of Rich Neck, contiguous to the land of Francis Peale, whose property lay along the Middle Plantation palisade and adjacent to what in 1693 became the College's property (Nugent 1969-1979:I:160, 242). The Kemp patent also noted that on June 13, 1642, 50 acres had been assigned to Captain Francis Pott, who had conveyed his land to William Davis. Davis also patented 500 acres at the head of Archer's Hope Creek and by 1639 had enlarged his holdings there to 1,200 acres (Nugent 1969-1979:I:143; Patent Book 2:51, 367). On October 10, 1645, when Thomas Hill patented his 600 acres at Rich Neck, he acknowledged that the tract was part of the 1,200 acres Richard Kemp had purchased from George Menefie (Nugent 1969-1979:I:160, 242). When a plat of Rich Neck was prepared in 1643, the Davis and Hill parcels were shown 15 (Senior 1643).16 By 1674, much of the Hill acreage was in the hands of Thomas Ludwell (see ahead)

On January 4, 1649, when Richard Kemp made his will, indicating that he was "sick and weak," he stated that he was residing at Rich Neck. He instructed his executrixes (his wife and daughter, both of whom were named Elizabeth) to sell his plantation to the best advantage and to confirm his sale of 50 acres in the Barren Neck on the "other side of the creeke" to George Read, his choice for deputy-secretary and a well connected longtime friend. Kemp told his widow to dispose of "my parte of the house Att Towne" and said that he wanted her and their daughter to leave Virginia. He died sometime prior to October 24, 1650, and probably was buried at Rich Neck. It is likely that Kemp's will was entered into the records of the General Court or the court of James City County shortly after his death; however, a copy did not reach authorities in England until December 6, 1656 (McGhan 1993:775).

By October 1650 Richard Kemp's widow, Elizabeth, had married Sir Thomas Lunsford, a hot-headed Royalist and friend of Sir William Berkeley. Elizabeth Kemp Lunsford retained Rich Neck until at least July 1654, and Lady Lunsford's property upon which she and Sir Thomas resided, was a frequently-used reference point in neighboring patents (Nugent 1969-1979:I:229, 282, 294, 298, 428, 465, 473; McGhan 1993:775). Richard and Elizabeth Kemp's daughter, Elizabeth, died prior to December 6, 1656, a which time Elizabeth Wormeley Kemp Lunsford, when presenting the late Richard Kemp's will to authorities in England, indicated that she was the surviving executrix (Withington 1980:323; McGhan 1993:775).

When surveyor John Senior prepared a plat of Richard Kemp's plantation, Rich Neck, on January 19, 1642/43, he indicated that the enlarged 4,332 acre tract abutted east upon the Middle Plantation palisade and Archer's Hope (College) Creek. Certain components of the property were identified with specificity. Shown prominently and identified with letters of the alphabet were branches of Archer's Hop.e Creek, the Middle Plantation palisade, and part of the horse path that later became Richmond Road and Duke of Gloucester Street. The letter K was used to identify the location of The Meadows and certain subunits of the Kemp tract were attributed to "Mr. Hill" (Thomas Hill), "Mr. Secretary" (Richard Kemp), and "Davies" (William Davis), to whom was attributed 50 acres. Also identified within "Mr. Secretary's 1st Division" was a cluster of three buildings, where archaeological features have been found and designated 44WB52. John Senior identified small parcels within Rich Neck that had been assigned to Thomas Hill and Edward Davies or Davis. Hill was credited with the northeasterly portion of Rich Neck's 1,200 acres; Richard Kemp retained the lower part. Moreover, the manner in which Hill's parcels are depicted (an aggregate of 600 acres) corresponds with the description given in his 1645 patent (Senior 1643; Nugent I:1969-1979:159-160). Rich Neck's boundary line extended from a certain point on the palisade, then turned in a northwesterly direction, paralleling the road that ran toward what became New Kent County. Kemp's line then turned sharply west., reaching the headwaters of Powhatan 16 Creek. At that point the boundary swung almost due south and then turned in a southeasterly direction back toward the head of Archer's Hope Creek.

In order to link the 1643 Kemp plat to modern topographic features, the 4,332 acre Rich Neck/Meadows tract's boundary lines were reconstructed to scale electronically, using not only John Senior's drawing but also the written data he had inscribed upon the plat. William Goodall's plat of Rich Neck, which in 1770 consisted of 3,865 acres, also was digitized. When the 1643 and 1770 plats were superimposed upon one another, it was found that despite the Ludwells' sale of acreage to Thomas Ballard I (the 330 acre college tract, which was conspicuously absent) and perhaps to others, the external boundaries of the consolidated Rich Neck and Meadows tracts as a whole had changed nominally since 643 (see the map "Rich Neck's boundaries as they were defined in 1643 and 1770"). As the 1770 rendering was more topographically sensitive than the 1643 version, and showed four main thoroughfares (what became Ironbound, Strawberry Plains, Richmond and Jamestown Roads), it was feasible to superimpose it upon a digitized topographic quadrangle sheet. This exercise made it possible to identify the boundaries of certain subunits of the enlarged Rich Neck tract: a 330 acre parcel that in 1674 and 1678 was delimited and sold to Thomas Ballard I and two other parcels (of 100 acres each) that in 1699 and 1707 were conveyed to the Rev. James Blair and then reabsorbed into Rich Neck.

Shown prominently and delimited upon the plats Robert Beverley I made for Thomas Ballard I in 1674 and 1678 as a 68 acre tract that belonged to Major John Page.17 The road from Middle Plantation to New Kent formed the southern and eastern boundary lines of the Page tract (see ahead). The boundaries of the 330 acre tract the Ludwells sold to Thomas Ballard I were identified, as were those of an adjoining 230 acre panel the Ludwells were keeping. Notations on the Beverley plat also provide useful information about the ownership of adjacent properties and cite boundary markers that are mentioned in contemporary patents. For example, reference was made to a hickory in Colonel Ballard's field (an indication that he owned land adjacent to the 330 acres he was purchasing) and a cherry tree "by Mr. Weekes" identified the property then owned by Robert Weekes, a long and narrow tract that abutted Rich Neck's north-east corner and formerly had belonged to Francis Peale (see ahead). Also within the acreage Thomas Ballard I was buying was "the negros quarter." The site of a spring and a bridge that crossed a branch of Archer's Hope Creek (at what became Rich Neck Mill and its pond, now Lake Matoaka) both were identified.

In late 1999, documentary research, which included a detailed title search and the use of nineteenth and twentieth century plats, was conducted on property upon which the United Methodist Homes, Inc. had an option. That acreage included distal portions of Rich Neck (as it was defined on the Senior and Goodall plats dating to 1643 and 1770) and of Powhatan Plantation, spanning the boundary line between the two properties, which was shown on a 1960 plat. This work reaffirmed the placement of the electronically reconstructed boundary lines of the.1643 and 1770 Rich Neck plats, which had been superimposed upon a digitized topographic quadrangle sheet. It also confirmed 17 the reliability of that interpretation, which was supported by the reconstruction of the two properties' chains of title.

Thomas Hill

On August 1, 1638, Mr. Thomas Hill secured a patent for a small lot in urban Jamestown. He was obliged to develop his property within six months (Patent Book 1:588; Nugent 1969-1979:I:95). Hill, a gentleman and merchant, conducted business with many of Virginia's most prominent families. He was in Virginia during the 1630s and was among those who sided with Governor John Harvey during the dispute with his councillors. In 1637, after Harvey had been reinstated as Virginia's governor, he had some of his old enemies' personal property seized and given to his supporters. Hill reportedly received some of Samuel Mathews' belongings. In January 1641 Hill served a term as James City's burgess, probably representing Jamestown (Withington 1980:52; Principal Probate Register 3 Seager; Sainsbury 1964:1:281; P.C. 2/50 f 428; C.O. 1/9 f 289, 543; 1/10 ff 73-74; Stanard 1965:61).

By April 1643 Thomas Hill had acquired 600 acres of Richard Kemp's 4,332 acre Rich Neck tract at Middle Plantation, Hill's two parcels were delineated when Kemp had Rich Neck surveyed in 1643. A small dwelling on Hill's property at Rich Neck has been identified by archaeologists. In April 1648 Thomas Hill, then described as a gentleman and planter, assigned his 3,000 acre Upper Chippokes tract (on the lower side of the James River) to Edward Bland. A few years later, he patented some land near the head of the Potomac River (Senior 1643; Nugent 1969-1979:I:143. 159, 175, 353). During Spring 1676 Thomas Hill made arrangements to lease Digges Hundred from its owner, Roger Green, who ultimately refused to vacate the property. The dispute ended up in court, where it was settled through arbitration. Hall may have moved to York County, for in December 1691 he (or another man of that name) served as a juror in the local court and on March 24, 1692, his deed for port land in Yorktown was acknowledged (McIlwaine 1924:386, 447, 447; York County Deeds, Orders, Wills 9:81, 123).

Thomas Ludwell

Thomas Ludwell, who was from Bruton in Somerset County, England, immigrated to Virginia during the 1640s and secured a patent for some land on the Chickahominy River. He also obtained a leasehold in the Governor's Land and acreage in Henrico County. In 1661 he became Secretary of the Colony, and he briefly served as interim treasurer. In April 1665, Ludwell updated officials in England on the progress that had been made on improving Jamestown and a year later, he reported upon the status of the colony's fortifications. One of his most interesting pieces of correspondence is his description of the August 1667 hurricane's impact upon Tidewater Virginia (Coldham 1980:37; McIlwaine 1924:492, 507; Hening 1809-1823:II:39; Nugent 1969-1979:I:145, 178, 429; Stanard 1965:21, 38; C.O. 1/19 f 75, 213; 1/ 0 f 218; 1/21 f 37, 113, 116, 282-283; 1/23 f 31; Sainsbury 1964:5:#975, #1250, #1410, #1506, #1508; McIlwaine 484, 486, 488).

Thomas Ludwell and a partner constructed a brick dwelling in Jamestown by adding onto an existing rowhouse (part of the structure known as the Ludwell Statehouse Group) and it 1667 they received a patent for the lot that enveloped their new dwelling. 18 Later, Ludwell purchased a neighboring unit (Nugent 1969-1979:II:57; Patent Book 6:223; McIlwaine 1924:514). In 1667, while Thomas Ludwell was Secretary, he was named the colony's escheator. He eventually became deputy surveyor and council president and succeeded Henry Randolph as clerk of the General Court (McIlwaine 1924:217-218, 239, 241, 247, 290, 331, 490-491, 510, 512, 515-516, 519; Hening 1809-1823:II:456). The trust Governor William Berkeley vested in Secretary Thomas Ludwell is evidenced by the considerable authority he had. Perhaps on account of the lucrative fees Ludwell earned as a government official, he was able to acquire substantial quantities of land, including Rich Neck and other acreage at Middle Plantation, and property in Henrico and Westmoreland Counties (McIlwaine 1924:205, Nugent 1969-1979:II:84, 92).

Thomas Ludwell returned to England in November 1674, after he had authorized Robert Beverley I to survey a 330 acre tract he intended to sell to Thomas Ballard I. He became ill during 1676 and died in the latter half of 1677. He bequeathed the bulk of his estate to his brother, Philip I, naming his sister (Jane) and nephew (Philip Ludwell II) as lesser heirs (McIlwaine 1924:519, 521; C.O. 1/41 f 35; Hening 1809-1823:II:456; Coidham 1980:37; Withington 1980:667). It was through this means that Philip Ludwell I came into possession of the Rich Neck tract, the northeasterly part of which in 1693 became the campus of the College of William and Mary.

Philip Ludwell I

Philip Ludwell I immigrated to Virginia around 1661, where he joined his brother, Thomas, then Secretary of the Colony. In 1667, the same year Philip was made a captain of the James City County militia, he wed the much-married Lucy Higginson Burwell Bernard, a wealthy widow, who had inherited and then sold a substantial quantity of land at Middle Plantation. She was the daughter of Captain Robert Higginson and had outlived Major Lewis Burwell II and Colonel William Bernard. Lucy and Philip Ludwell I resided at Fairfield, the Burwell home on Carter's Creek in Gloucester County, and were living there in 1672 when on Philip II was born. They also had a daughter, Jane, who married Daniel Parke II, the notorious rake and governor of the Leeward Islands. Between 1673 and 1675 Lewis Burwell III (Lucy's son by her first husband) probably took possession of Fairfield, for Lucy died and young Burwell (his father's sole heir) came of age and married for the first time. It was likely then that Philip Ludwell I vacated Fairfield and moved to James City County, probably into his brother's unoccupied home at Rich Neck, or one of his rowhouse units at Jamestown. Philip began patenting substantial quantities of land in the colony (Meyer et al. 1987:237-238; Shepperson 1942:453; Stanard 1965:21, 40; Parks 1982:225; Nugent 1969-1979:II:33, 132; McIlwaine 1924:355).

During the mid-1670s Philip Ludwell I assumed an increasingly prominent role in public life. In November 1674, when Secretary Thomas Ludwell set sail for England, he authorized Philip to serve as his deputy. During the mid-1670s Philip Ludwell I made numerous appearances in the General Court, where he audited accounts, filed law suits, and provided testimony. In 1675 he was named to the Governor's Council, which office he retained until 1677. He also was the colony's-surveyor general. The Ludwell brothers were two of Governor Berkeley's most loyal supporters throughout Bacon's 19 Rebellion and its turbulent aftermath. Philip was among those who accompanied Berkeley when he fled to the Custis plantation, Arlington, on the Eastern Shore, and afterward he reported that his goods and those of his ward (his Burwell stepson) had been plundered. He wrote a description of Bacon's Rebellion and was among those who in March 1677 witnessed Sir William Berkeley's will. He was considered a member of the "Green Spring faction," a group who remained highly partisan after the popular uprising was over. Ludwell's views, which he frequently voiced, placed him at odds with Lt. Governor Herbert Jeffreys and he also was highly critical of Governor Francis Howard, Lord Effingham. Ludwell was suspended from the council but began serving as a burgess for James City County. He married the widowed Lady Frances Berkeley and eventually became her heir. After his death, the Berkeley property descended through Philip Ludwell I's line (Meyer et al 1987:237-238; Shepperson 1942:453; Bruce 1893-1894:175; Stanard 1965:21, 40, 86; McIlwaine 1925-1945:I:88, 468, 510; 1924:382, 385, 515-516, 520, 523; C.O. ½ f 304; 3/1355 ff 152-155; 5/1357 ff 260-261, 271-276, 270, 283; Parks 1982:225; Hening 1809-1823:II:560; Beverley 1947:96; Sainsbury 1964:9:414).

During the latter half of 1677, Thomas Ludwell died, leaving the bulk of his estate to his brother, Philip I, and naming his sister, Jane, and nephew, Philip Ludwell II, as heirs (McIlwaine 1924:519, 521; C.O. 1/41 f 35; Hening 1809-1823:II:456; Coldham 1980:37; Withington 1980:667). It was through this means that Philip Ludwell I came into legal possession of the Rich Neck tract, the northeasterly part of which eventually became the site of the College of William and Mary. Philip Ludwell I retired to England around 1694, leaving his vast Virginia estate in the care of his son, Philip II, who had just come of age (McIlwaine 1918:56, 86, 97; 1905-1915:1660-1693:245, 282; 1925-1945:I:40; Ambler MS 62; Patent Book 8:315; Shepperd 1980:7).

Thomas Ballard I and Thomas Ballard II

Thomas Ballard I, who was born in England, in 1664 serves a James City County justice of the peace and in 1670, took his turn as sheriff. In 1666 he became James City's burgess, representing the county rather than Jamestown, the capital city which had its own delegate. In 1670 Ballard was named to the Governor's Council. He was a respected citizen who frequently was called upon to audit accounts and arbitrate disputes (Stanard 1965:39; Hening 1809-1823:II:249-250; McIlwaine 1924:211, 218, 235, 329, 340, 342, 373, 516).

Because Thomas Ballard I remained loyal to Governor William Berkeley, the rebel Nathaniel Bacon declared him a traitor. In September 1676, when Bacon's men captured the wives of several prominent men and used them as a human shield while building a fortification near Glass House Point, Thomas Ballard I's wife, Anna, was one of the women behind whom the rebels hid. Early in 1677, when the king's troops were sent to the colony to restore order, Ballard was ordered to find land for them to use to grow corn for subsistence. He continued to serve as a councillor after Bacon's Rebellion had been quelled and sometimes clashed with Lieutenant Governor Herbert Jeffreys. During the 1680s Ballard served as a burgess. In 1674 Thomas Ballard I made arrangements to purchase 330 acres of land from Thomas Ludwell, acreage that was part of Rich Neck and was located at Middle Plantation, abutting the roads to New Kent and 20 Jamestown. The boundary line of the property Ballard intended to purchase are shown on plat prepared by Robert Beverley I in 1674 and 1678. Together, the acreage Thomas Ludwell and his heir, Philip Ludwell I, conveyed to Ballard totalled only 284 acres, when ravines and other low-lying areas are excluded. A notation on both plats, which identifies as a boundary marker a "hickory in Mr. Ballards feild," reveals that Thomas Ballard I was purchasing some land adjacent to a tract he already owned (see "Middle Plantation, 1699/1700"). Surveyor Robert Beverley I made reference to "the negroes quarter" but didn't disclose whether it was on the property the Ludwells were selling or on what already belonged to Ballard. Thomas Ballard I died in Virginia in 1689 and in1693, officials of the College of William and Mary purchased his estimated 330 acres from his son and heir, Thomas II (Force 1963:I:9:8; Sainsbury 1964: 10:341; C.O. ½ f 304; McIlwaine 1905-1915:1660-1693:72; 1918:93; Beverley 1674, 1678; Stanard 1965:39, 84).

In 1699, when Theodorick Bland (1699) prepared a plat upon which he identified Williamsburg's external boundaries, he pinpointed the site at which a stone boundary marker had been placed, to signify the eastern limits of the college's property. That stone was situated 10 poles (165 feet) east of the intersection formed by Henry and Duke of Gloucester Streets. Thus, when Williamsburg first was laid out, part of the college property lay within the city's bounds (see "Middle Plantation, 1699/1700").

On January 12 and 13, 1720, the trustees of the city of Williamsburg conveyed a dozen lots to merchant Thomas Jones, two of which were Lots 360 and 361 in Block 15. Thirty years later, Jones referred to the two parcels as his "college lots," thereby acknowledging (without explanation) their connection with William and Mary (York County Deeds, Administrations, Bonds 3: 322-323; Jones Papers). As Block 15 lies west of the boundary stone that in 1699 marked the easternmost limits of the college's property, it is likely that Thomas Jones purchased two of the lots that were laid out upon acreage taken from the college when the city of Williamsburg was laid out. Based upon this interpretation, Blocks 15 and 5 are derived from land that between 1693 and 1699 was part of the 330 acre college tract, whereas the 68 acre trait that Colonel John Page gave to his son, Francis, in 1679 gave rise to Blocks 23 and 31. Likewise, Blocks 14 and 22 include land that during the early 1640s belonged to John Saines. Later, the land that became Block 14 was in the possession of Francis Peale, Robert Weekes and probably the Brays.

Governor Francis Nicholson

On March 6, 1705, Governor Francis Nicholson informed his superiors that it was absolutely necessary for him to live in Williamsburg, so that he could see that oversee the construction of the new capital city's public buildings. He said that he had been living in the same house ever since he moved to Williamsburg which was then the only dwelling available. He indicated that he was renting it from the college for far more than it as worth and that if he died or left the colony, his lease would become null and void. He said that Mr. Harrison (probably Benjamin Harrison Jr., who then had four houses in 21 town)18 had offered to sell a dwelling to him or rent it at an exorbitant annual rate, unless he signed a seven year lease. Nicholson added that he has been willing to give Harrison 40 pounds sterling per year for two or three years, even though "it daily decays," but Harrison had refused his offer. He said that other than the accommodations he was renting, "there is no other house in town, only Mr. Harrison's."19 Governor Nicholson tried to quash rumors that he was having an improper relationship with his housekeeper, and that his servants were poorly fed. He insisted that although his people often had "but one dish a day," it was generally known that they were adequately provided for (Sainsbury 1964:22:490-431).

The discovery of wine bottle seals bearing the letters "FN" on the acreage later occupied by the Public Hospital, raises the possibility that the dwelling Nicholson was renting from the college was located in that vicinity, for it was in close proximity to college-owned land. Governor Francis Nicholson held office in Virginia until August 1705. He was chief executive of Nova Scotia for several weeks in 1713 and finally, in 1721 he became governor of South Carolina. He died in March 1728, never having married (Raimo 1980:482-483; Stanard 1965:17, 42).

John Young

In the wake of the October 29, 1705, fire that destroyed the College of William and Mary's main building, witnesses were summoned to testify about what they saw the night of the blaze. At issue was whether arsonists had been at work and in what portion of the building the fire was first seen. One of the individuals called upon to testify was Williamsburg tavern-keeper John Young, whose establishment provided a good view of the college building's south side. Another was Young's maid servant, Susanna Hooper. A third observer, William Young, who had ridden into town on the road from New Kent (the forerunner of Richmond Road), said that after he had passed by the college and turned his horse toward Mr. Jennings' quarter and Jamestown, he noticed that the south side of the building was on fire. He then reversed is course and hurried back to John Young's, tavern, to alert its occupants that the college was ablaze. Young said that he saw three men "in pretty good apparell" running away from he college, as though they were fleeing from the scene. Colonel Edward Hill, who had been an overnight guest at the college, said that he hurried from the burning building by means of its south door. Then, in an after-thought, he decided to return by the same ro[ute] to retrieve some of his belongings. He said that he carried his personal effects "almost as far as ye road ye cross gong to Jno. Young's," i.e., Jamestown Road (Goodwin 1954:106).

Susanna Hooper testified that while she was in the kitchen of John Young's tavern, William Young came to the door, "crying out ye College is on fire, why don't you get up 22 and save yrselves, else you'l be burnt." She said that when she looked out, she saw flames that were "on ye south end near Mr. Young's house." Susanna then went to an upstairs window on the north side of the tavern, from which vantage point she "perceived the fire on ye south side of ye Cupulo." Ordinary-keeper John Morot also testified that the blaze was visible from his house and two men staying "in the Countrys houses at ye Capitol" saw it (Goodwin 1954:108-112).

The eyewitness accounts that are available suggest strongly that John Young's tavern was in relatively close proximity to the college's main building. As the blaze commenced on the south side of the structure and was visible from an upstairs window on the north side Young's tavern, and as his establishment was across the road from the college, it was located within in the James City County side of Williamsburg, probably between Jamestown Road and South Boundary Street.

Cultural Features Potentially Associated the Ballard/College Tract

When the plats prepared by Robert Beverley I in 1674 and 1678 were reconstructed to scale electronically and the boundaries of the 330 acre tract that Thomas Ballard II sold to the College of William and Mary were delimited, the college tract's easternmost boundary line was placed just east of the intersection of Henry and Duke of Gloucester Streets. As "FN" bottle seals have been recovered from a domestic site (the so-called Nicholson Site) that is located in very close proximity to the college's property on the east side of Jamestown Road, the possibility exists that they are associated with the. house Nicholson was renting from the college. That Thomas Jones, who during the 1750s referred to Block 15 Lots 360 and 361 as his "college lots," lends support this hypothesis.

A tavern operated by John Young probably stood near the intersection formed by Duke of Gloucester Street and Jamestown Road. In late October 1705, when the college's main building caught on fire, there was general agreement that flames first were seen on the south side of the building. Some of those who testified expressed their concern that John Young's tavern, across the road, would be set ablaze. A maid servant of Young's, who was peering from an upstairs window in the north end of Young's tavern, also reported seeing the fire. A man on horseback, who rode into town via the road from New Kent, said that he passed by the college and then continued on toward Jamestown. When he saw the fire at the college, he hurried back to Young's tavern to awaken the guests. All of these accounts suggest strongly that Young's tavern was relatively close to the college's main building and probably was on the east side of Jamestown Road.

The Rev. James Blair

The Rev. James Blair was born in Scotland in 1655 and received the Master of Arts degree from the University of Edinburgh in 1673. He was an ordained Anglican minister and moved to England around 1682, where he became acquainted with the Bishop of London. In 1685 he immigrated to Virginia. On October 21, 1687, he patented 453 acres of land in Henrico County at Varina, where the Henrico Parish glebe was located, and in Apri1 1690 he and two other men patented a 130 acre strip of land between the glebe and Two Mile Creek, in anticipation that their acreage would be selected as the site of a planned town. It was. It 1689 the Bishop of London designated the Rev. James Blair as 23 his Commissary or official representative in Virginia and in that capacity, Blair began holding meetings of the colony's clergy. At those convocations, the idea originated of having a college in Virginia, where clergy could be trained. Blair was commissary for 54 years (Hartwell et al. 1940: xxii-xxiv; Goodwin 1954:25).

The Rev. James Blair was one of William Byrd II's close friends and his brother, Archibald, was a highly esteemed physician. In 1687 the Rev. Blair married Sarah, the sister of Philip Ludwell I, thereby allying himself with Virginia's planer elite (Hartwell et al. 1940:xxviii). Sarah's adamant refusal to use the word "obey" when taking her wedding vows created quite a stir (C.O. 5/1339 ff 36-37; Byrd 1941:25; Goodwin 1927 251). In 1689 the Rev. James Blair was appointed to the Governor's Council. He served as rector of James City Parish from 1694 until 1710, when he took over the ministry of Bruton Parish, and stayed there until his death in 1743. On February 4, 1698/99, while the Rev. James Blair was a councillor, he and his wife purchased 100 aces from his father-in-law, Philip Ludwell I, land that was part of Rich Neck and close to the college. The Blairs already were in possession of the property when they bought it. On August 5, 1707, James Blair commenced leasing from Philip Ludwell II an adjoining 100 acres that lay to the south and abutted directly upon the college property. Both agreements specified that if Blair and his wife failed to produce heirs, the property would revert to the Ludwells, which in fact, is what occurred. Both Blair parcels are depicted on the map entitled "Middle Plantation, 1699/1700," where they are collectively labeled "Ludwell to Blair." Together, they comprise the tract identified on Robert Beverley I's 1674 and 1678 plats as Colonel Ludwell's 230 acres. The boundary markers cited in the deeds from the Ludwells to the Blairs are the same ones identified on Robert Beverley I's plats.20 The Rev. James Blair, Henry Hartwell and Edward Chilton, who were asked to report on conditions in Virginia, prepared a treatise that was published (Stanard 1965:42; McIlwaine 1925-1945:I:325, 360, 440; Nugent 1969-1979:II:313, 341; Ludwell 1698, 1707; Beverley 1674, 1678; Sainsbury 1964:15:584, 655).

The Rev. James Blair quarreled openly with three of Virginia's highest ranking officials (Governor Edmund Andros and Lieutenant Governors Francis Nicholson and Alexander Spotswood) and by using his influence with the Bishop of London, was instrumental in having them recalled. In 1697 Blair declared that Governor Andros had wasted a great deal of money by building a gun platform at Jamestown and a brick powder magazine that was vulnerable to attack. At the root of Blair's complaint may have been Andros' stubborn refusal to vacate his lease for a rental property that the clergyman wanted to use for the accommodation of the college's grammar school students. In 1704, Blair complained about Nicholson, whom he said behaved badly, and in 1718 he had problems with Spotswood, who wanted him removed from the Council. Governor William Gooch also disliked Blair and described him as "a very vile old ffellow" (Hartwell et al. 1940:xxiv-xxv) . In 1715, when the college's main building burned, he had an overseer, William Eddings, in residence upon his property. Eddings testified that he could see that the fire coming from the port side of the cupola from a 24 vantage point in his corn field. This suggests that Eddings' dwelling was relatively close to the campus of the college (Bruce 1899:277-281). From September 1740 to July 1741, the Rev. James Blair, as Council president, served as acting governor. He died on November 14, 1743, and was interred at Jamestown, next to his wife, Sarah, who had predeceased him by 31 years (Perry 1969:I:14; Sainsbury 1964:22:158; C.O. 5/ 307 f 22-23; 5/1318 f 268; Stanard 1933:19, 61; 1965:19). As the Blairs failed to produce children, the property they had procured from the Ludwells reverted back to them and again became part of Rich Neck.

Archaeological Features Associated with the Rev. James Blair's Property

In 1699 Blair and his wife bought from Philip Ludwell I 100 acres that lay within northerly part of the acreage attributed to the Ludwells and shown on Robert Beverley I's 1674 and 1678 plats. They occupied the property for a time and in 1707, when they leased an adjoining 100 acre tract, were said to be in residence upon the land they had acquired earlier on. This suggests than the Blairs lived upon the northerly 100 acres. The 101 acres they leased lay directly below it and abutted the 330 acre tract Thomas Ballard II sold to the College of William and Mary in 1693.

THE SAINES/PEALE/WEEKES LANDHOLDINGS

John Saines